What Designing for Vulnerability Teaches Us About UX Everywhere

In the previous article, I explored how Calm UX becomes essential when digital products start predicting, recommending, and acting on users’ behalf. As systems grow more intelligent and autonomous, clarity, control, and psychological safety are no longer optional—they are prerequisites for trust.

Healthcare takes this one step further.

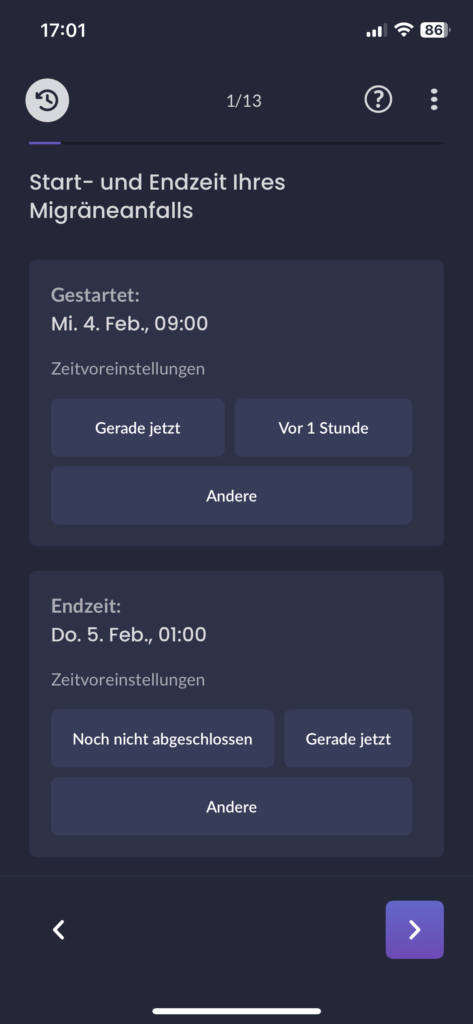

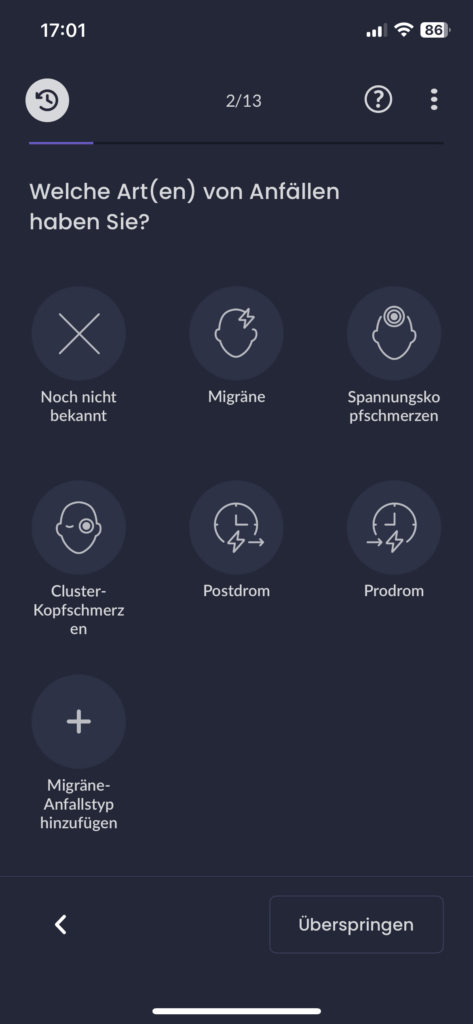

Healthcare is often treated as a special category in UX design—a domain with its own rules, constraints, and sensitivities. But it is not defined by different principles. It is defined by a different context of use. Healthcare doesn’t require new UX fundamentals; it requires existing ones to perform under pressure.

In healthcare contexts, users are rarely relaxed, curious, or exploratory. They interact with products while anxious, cognitively overloaded, emotionally vulnerable, or afraid of making mistakes. That makes healthcare products a powerful stress test for UX as a discipline.

If an interface fails under these conditions, it doesn’t fail because healthcare is “special.” It fails because the design was never truly calm, clear, or human-centered to begin with.

Healthcare as an Extreme UX Environment

Much of mainstream UX quietly assumes ideal conditions:

- stable attention

- emotional neutrality

- tolerance for exploration

- low cost of errors

Healthcare strips these assumptions away.

Users engage with health products while processing emotionally charged information, navigating uncertainty and risk, experiencing cognitive fatigue or distress, and fearing irreversible consequences. Under these conditions, even small ambiguities or unnecessary decisions can escalate into anxiety. This reveals a crucial insight:

Many interfaces rely on idealized users. Healthcare reveals real ones.

Calm UX becomes critical here not because healthcare is unique, but because it removes the safety buffer that often hides poor UX elsewhere. When attention is scarce and emotional stakes are high, only designs that genuinely reduce cognitive load and uncertainty can hold up.

Where Healthcare Reveals Broken UX Assumptions

Healthcare UX tends to fail in the same places where mainstream UX quietly struggles—but the consequences are far more visible. Designing for healthcare also means designing for neurodivergence and mental health, which exposes fundamental truths about how people actually interact with systems under strain.

Users with ADHD, anxiety, autism, or depression are more sensitive to cognitive load, less tolerant of ambiguity, more affected by interruptions, and more easily disoriented. These are often treated as edge cases, but they are not. They represent states that all users enter under stress—and healthcare places everyone in that state.

This is where many interfaces break down:

- alarmist language that escalates uncertainty instead of explaining it

- silent systems that leave users unsure whether an action succeeded

- dense information displays that prioritize completeness over comprehension

- binary outcomes presented without context or confidence framing

Outside healthcare, these issues cause frustration. Inside healthcare, they lead to anxiety, mistrust, and hesitation.

Calm UX reframes these moments by separating information from urgency, acknowledging uncertainty rather than hiding it, layering complexity instead of front-loading it, and reinforcing user agency at every step.

Calm UX as an Opportunity in Healthcare

In healthcare, Calm or Mindful UX is not about “being nice”—it’s about designing with a clear understanding of human limits. This means explicitly considering the user’s emotional and cognitive state: how much attention they can realistically give, how much information they can process, and how uncertainty might amplify fear or hesitation. It also means designing systems that reassure without misleading, guiding users without overwhelming them.

Focusing on Calm UX in healthcare doesn’t just improve health products. Much like accessibility features, it advances UX practice as a whole by grounding design decisions in real human constraints—and by bringing those improvements into everyday products where everyone can benefit.

My Conclusion to Calm UX and Calm Technology

The principles of Calm Technology are not a new discipline, but are already deeply embedded in established UX approaches—across digital and physical product design, and in domains such as healthcare and AI. UX has reached a level of maturity where the focus is no longer only on efficiency or fixing major usability issues, but on consciously considering people and their emotional experience throughout the process. Calm Technology makes this focus explicit, much like accessibility does, reminding us that user-centered design cannot meaningfully exist without these principles.

References:

- https://www.nngroup.com/articles/minimize-cognitive-load

- https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-advice-comprehensive-regulatory-assistance/human-factors-and-medical-devices

- https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2025/05/designing-calm-ux-principles-for-reducing-users-anxiety.php

- https://www.w3.org

- van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & Sweller, J. (2010): “Cognitive load theory in health professional education”

AI Assistance Disclaimer:

AI tools were used to improve grammar and phrasing. The ideas, examples, and content remain entirely the author’s own.