Background

This week I had a situation that perfectly illustrated why I chose this topic. I was explaining some functionalities of a new app to my grandfather. He has always been very tech-savvy, he still works on his own website but even he struggles with certain concepts from time to time. He often tells me that everything takes him much longer than it used to and even when I show him a quicker or easier way to do something, he still sticks to the method he already knows. I believe this is partly a matter of habit and partly a reluctance to change something that “still works.”

What surprised me most was watching him interact with the app after my explanation. I assumed that once I had shown him how the app worked, it would be straightforward. But when he tried it on his own, he had to stop and ask for help at many points. It made me realize how much prior knowledge and digital literacy designers unconsciously expect from users, even when the interface seems simple to us.

This small moment showed exactly why designing for older adults matters: even motivated users with experience and interest in technology can struggle when interactions are not intuitive, forgiving or aligned with their mental models.

But here comes the real question: Is the problem rooted in the design of digital products or in the mental models that older adults bring with them? In other words, should we focus on improving the interfaces or on helping older people build the conceptual frameworks they need to understand how technology works in the first place?

Research

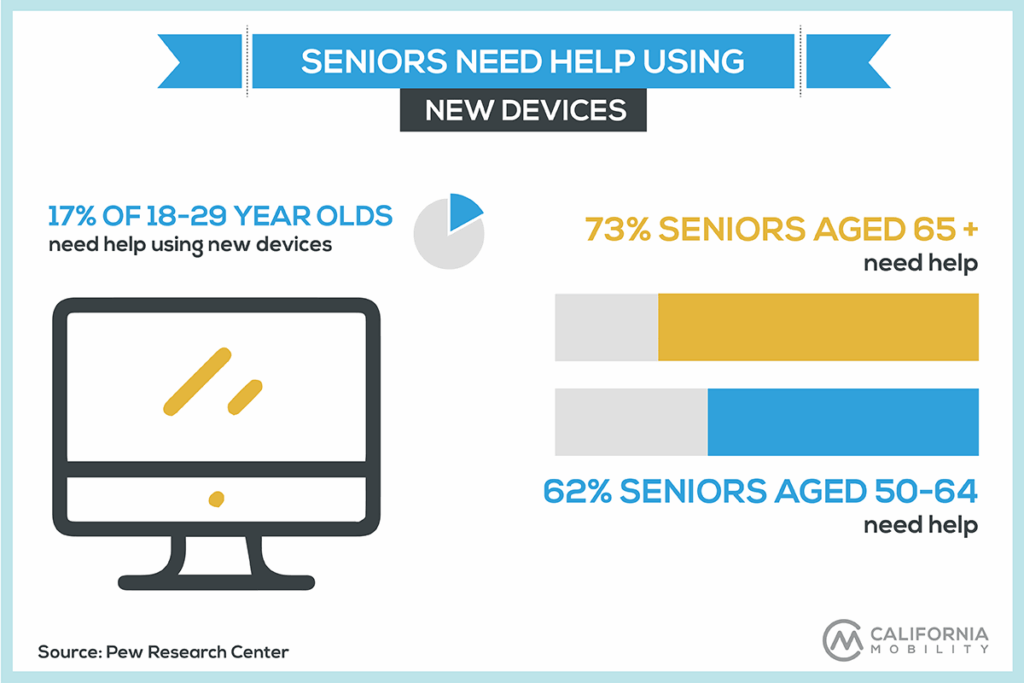

Problems older adults face with technology usually come from two sides: the design of the technology and the way older people understand and process information. When these two sides don’t match, it leads to confusion and mistakes. [1][3]

Many digital products simply aren’t designed with older adults in mind. This creates barriers that make technology hard to use.

- Interfaces that feel cluttered or complicated: When apps have too many features or unclear layouts, older adults struggle to find what they need.[3]

- Physical design that clashes with age-related changes: Small buttons, close-together touch targets or gestures like pinching and swiping can be difficult due to reduced vision, motor skills or dexterity.[3]

- Unclear icons: Small, abstract or unfamiliar icons can be hard to recognize. Older adults often expect bigger, more descriptive labels instead of symbolic icons. [3]

- Inconsistent design: If the interface doesn’t behave in predictable ways, it breaks the user’s expectations. This lowers trust and makes people feel unsure about what will happen next. [5]

(Planned) Sources

[1] D. Orzeszek et al., ‘Beyond Participatory Design: Towards a Model for Teaching Seniors Application Design’, arXiv [cs.CY]. 2017.

[2] L. Kane, “Usability for Seniors: Challenges and Changes,” Nielsen Norman Group, Sep. 08, 2019. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-for-senior-citizens/

[3] G. A. Wildenbos, L. Peute, and M. Jaspers, ‘Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: A literature based framework (MOLD-US)’, International Journal of Medical Informatics, vol. 114, pp. 66–75, 2018.

[4] J. Nielsen, “Usability for Senior Citizens: Improved, But Still Lacking,” Nielsen Norman Group, May 28, 2013. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-seniors-improvements/

[5] Thefinchdesignagency, “Building User Trust in UX Design: Proven Strategies for Better Engagement,” Medium, Feb. 05, 2025. https://medium.com/@thefinchdesignagency/building-user-trust-in-ux-design-proven-strategies-for-better-engagement-c975aa381516