In the last post, I proposed the question: have there been experimental tests to try to overcome [learning body and silk awareness off the ground] in a different way?

Consider the following image of a split in the air [1]:

Image from Silks Stars, 2025. [1]

To get into a Carpenter’s square (unstandardized name), the first step the aerialist must do is turn her body in between the 2 pieces of fabric. Then, she must go in front of one piece of fabric and then hook her foot in it, like so:

Own gif, 2024.

However, this begs the question that this post is titled after, and exemplifies the interaction design problem once again. In this specific example, the direction of the 2 turns is explained as “towards the pinky toe you see”, since this is a reference relative to your body and not relative to the environment. The next moves are explained as “stand up, bring your hand up to the silk as if you had a fever, go in front of it, and bring the foot that you’re standing on to the top of the silk.”

3 other experimental studies address the body awareness problem through external stimuli regarding vision, sound, or both. These are explained in the next paragraphs.

In an experimental study, [2] created technology training probes to “augment proprioceptive information and make it available through exteroceptive senses.” These consisted of an embedded system sewn into different wearable fabrics, each designed specifically for different body parts and circus disciplines [2].

Image from Márquez Segura et al., 2019. [2]

In training with the wearable devices, [2] discovered that focusing on external stimuli made children enjoy the exercise more and improved their overall performance, specifically: children were focused more, were more aware and in control of their posture, were more aware of their movement patterns, could maintain challenging positions longer, were able to engage and relax different body parts easier, had more endurance, could move past fear, and enjoy the exercise more. This study wasn’t focused on aerial silks specifically, but it proved that, in floor acrobatics, externalizing proprioception through a range of lights and sounds helped children with sensory-based motor disorder [2].

In another study, [3] created an aerial hoop which “generates auditory feedback based on capacitive touch sensing.” They added electrodes to a normal hoop in order to detect different touch data, which is then turned into auditory feedback through non-obstructing hardware housed in a wooden box [3].

Image from Liu et al., 2021. [3]

The study found that the extrinsic auditory feedback helped artists to be more aware of the quality of their movements, including details that they would normally not pay attention to [3]. However, this study was done with expert hoop artists, which mentioned it would not be an accessible tool for beginners who are at first barely learning what their body must do [3].

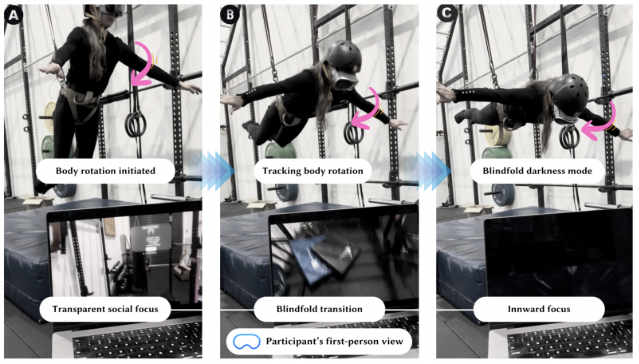

In a third experiment, [4] used a head-mounted VR headset to partially blind participants while being suspended from a 2-point harness, as shown in the picture.

Image from Topaz et al., 2025. [4]

While not specifically designed for circus disciplines, the study found that when they took vision away from participants, they were forced to focus more on their internal sensations, muscles, and body movements, increasing their bodily awareness [4]. Two relevant quotes from participants of the study were as follows: “The black environment helped me focus on the muscles to regain balance” and “When I used to perform, I was far above the audience. Using the blindfold application reminded me how stimulating and distracting I find the outside world. It felt very peaceful and focused to be in the virtual world alone with my body” [4].

–

[1] “Flexibility,” Silks Stars. Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online.] Available: https://www.silksstars.com/category/foundations/flexibility/

[2] E. Márquez Segura, L. Turmo Vidal, L. Padilla Bel, and A. Waern, “Circus, Play and Technology Probes: Training Body Awareness and Control with Children,” Proceedings of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, vol. 1, pp. 1223-1236, June 2019.

[3] W. Liu, A. Dementyev, D. Schwarz, E. Fléty, W.E. Mackay, M. Beaudouin-Lafon, and F. Bevilacqua, “SonicHoop: Using Interactive Sonification to Support Aerial Hoop Practices,” Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, vol. 1, pp. 1-16, May 2021.

[4] A. Topaz, M.F. Montoya, R. Patibanda, J. Andres, and F. Mueller, “Blindfolded in the Air: Towards the Design of Interactive Aerial Play,” Proceedings of the First Annual Conference on Human-Computer Interaction and Sports, vol. 1, pp. 1-16, November 2025.