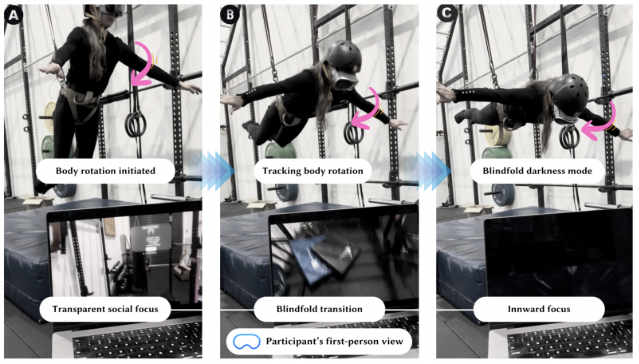

[1] states that “a central puzzle that people face, from a design perspective, is how to make communication possible that was once difficult, impossible or unimagined.” This problem is exacerbated when the communication topic is one’s own body awareness and proprioception – and it’s an even bigger problem when you add the extra element of being suspended in the air.

I believe that a possible solution to my identified design problem is redesigning the communication strategies used in aerial silks teaching, but to do so, we must first understand what communication design actually is. [1] defines it as “an intervention into some ongoing activity through the invention of techniques, devices, and procedures that aim to redesign interactivity and thus shape the possibilities for communication.” We, as designers, must design communication strategies in the preferred form of interactivity of the receiver, eliminating the nonpreferred forms [1].

According to [2], good communication must be effective (achieving the objective), appropriate (conforming to the rules of a situation), satisfying (fulfilling expectations), efficient (achieving the valued outcomes relative to the amount invested), verisimilar (having clearly understood symbol-referent links), and task-achieving (accomplishing the correct interpretation). It is also located in perception rather than in behavior [2]. This means that good communication is evaluated by people’s subjective perception that a communicator and their performance are appropriate and effective [2].

Communication can be classified by channel (i.e., the medium, means, manner, and methods): verbal or non-verbal [3]. Verbal communication can be either oral (either face-to-face or via a distance) or written, whereas non-verbal communication is more subtle [3]. Non-verbal communication consists of facial expressions, gestures, body language, eye contact, touch, space, and personality [3]. Communication can also be classified by style: formal (as in, within the professional environment) or informal (also called word-of-mouth) [3].

In the context of aerial silks, effective communication must:

- Reference mutually understood signifiers for basic movements (e.g. Footlock, hip key, S-wrap, etc.)

- Be both visual (observation of a teacher/video) and verbal (naming the steps)

- Be memorable (or in its defect, have a communicator repeating the steps while the aerialist does the figure)

Plus, I would add that communication in aerial silks does not terminate once the communicator gives the steps to the aerialist; but rather, it ends once the aerialist has climbed the silk and actually felt the figure in the air.

–

Sources:

[1] M. Aakhus, “Communication as Design,” Communication Monographs, vol. 74, pp. 112-117, March 2007.

[2] B. H. Spitzberg, “What is Good Communication?,” Journal of tbe Association for Communication Administration, vol. 29, pp. 103-119, January 2000.

[3] R. Kapur, “The Types of Communication,” Multidisciplinary International Journal, vol. 6, pp. 1-7, December 2020.