The productivity continuous! And for once, I finally overcame my procrastination.

At least I think so… Let’s dive in!

In my previous blog posts, I introduced emotional design and explained why emotions play such an important role when we interact with products and interfaces. I also mentioned the three levels of emotional design described by Don Norman. In this post, I want to move a bit away from theory and talk about how emotional design shows up in everyday situations that many of us know very well.

When I started paying attention to emotional design, I realised how often design influences my mood without me even noticing. Sometimes it makes me feel excited, sometimes relaxed, and sometimes just annoyed enough to close an app or website immediately.

Visceral Design

aka “Love (or Hate?) at First Sight”

Visceral design is about first impressions. It is that very first moment when you see something and instantly have a feeling about it (vgl. Norman 2004, S. 19).

I notice this especially with book covers. When I browse through books in a store or online, I usually decide within a few seconds whether a book interests me or not. Some covers feel inviting right away. I cannot always explain why, but they create a certain mood that makes me want to take a closer look. This reaction happens automatically, without much thinking, which shows how strongly visceral design influences first impressions.

On the other hand, I have also experienced the opposite. Some posters or websites feel overwhelming in an instant. Too many colours, different fonts, a confusing layout. Instead of feeling curious, I feel stressed. In these moments, I often leave within seconds, even if the content might actually be useful. The first impression already ruined the experience.

Behavioural Design

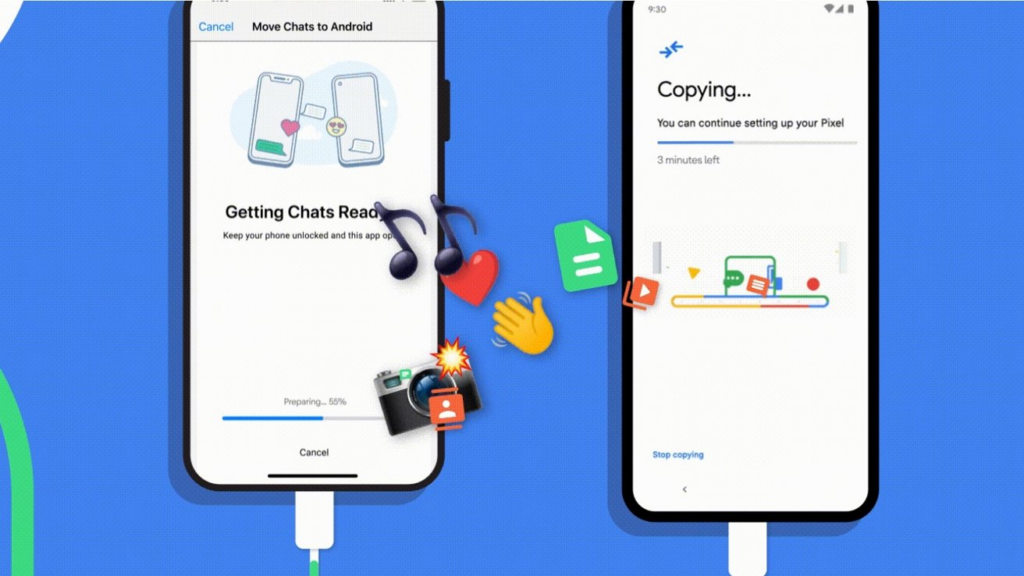

Behavioural design becomes noticeable once we start using a product. This is where emotions like satisfaction or frustration show up very quickly (vgl. Norman 2004, S. 23).

A positive example I often think about is the onboarding experience of a new smartphone. Turning on a new device usually feels exciting, but it could also be overwhelming. Step-by-step guidance, clear instructions, and friendly messages make the setup process feel easy and reassuring. Instead of feeling lost, I feel supported and in control, which makes the whole experience enjoyable.

A negative behavioural experience is something I know all too well. Apps or websites that do not work the way I expect them to. Buttons are hard to find, settings are hidden, or error messages appear without explanation. Even if the design looks nice, these moments quickly turn curiosity into frustration. And once I am frustrated, I rarely want to keep using the product.

Reflective Design

Reflective design is about how we remember an experience later and what meaning it has for us (vgl. Norman 2004, S. 38).

A very strong positive example for me is the video game It Takes Two. The game is designed to be played together and focuses heavily on cooperation and communication. What stayed with me was not only the gameplay, but the shared experience itself. I remember who I played with, the conversations we had, and how the story made us feel.

Negative reflective experiences usually come from what happens after using a product. Poor customer service, hidden costs, or broken promises often leave a bad feeling. Even if the product worked fine, these memories dominate. When I think back, I mostly remember the frustration.

Thinking about these examples made me realise that emotional design is not abstract at all. It shapes how we feel in the first second, during use, and long after an experience is over.

For designers, paying attention to these emotional moments can make a huge difference. Emotional design can turn everyday products into meaningful experiences or, if done poorly, into something people want to forget as quickly as possible.