#slowness #slowliving #slowinteraction #digitalcalm #calmtechnology

In this part of my research, I would like to review apps and digital products that, in my opinion, practice the basic principles I discussed in my previous article, or that align with the ideology of “slowness” and promote it to the masses.

I have tried all of these apps myself, and I will try to draw objective conclusions and also point out my observations while using the app.

🌳 Forest: Stay Focused

The app was created in 2014 in Taiwan by the Seekrtech team. The team was inspired by digital overload and the habit of constantly checking our phones. Unlike strict blockers, including iPhone blockers, Forest offers a beautiful, metaphorical approach to managing our attention, namely through the idea of growing and caring for a tree.[1]

How does it work ❔

The user plants a virtual tree, and the tree grows for a set period of time. If you exit the app or use your phone while the tree is growing, it will immediately die. In this way, attention is transformed into a process that requires time, patience, and consistency.

The interface is minimalistic and visually calm—almost nothing happens during a session in the app, which reduces cognitive load and supports slow and steady concentration.

Forest makes pausing and waiting a valuable experience rather than an interface flaw. The app demonstrates that slowness can be not an obstacle, but a conscious design tool that supports user attention and well-being.

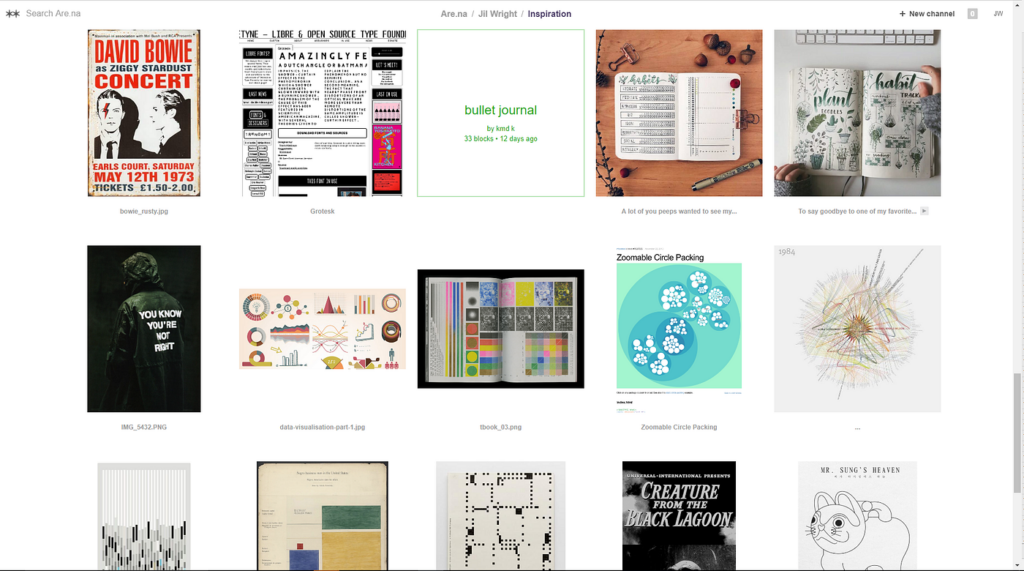

🌟🌟Are.na (knowledge & research platform)

Are.na is an online social networking community and creative research platform founded by Charles Broskoski, Daniel Pianetti, Chris Barley, and Chris Sherron. Are.na was built as a successor to hypertext projects like Ted Nelson’s Xanadu, and as an ad-free alternative to social networks like Facebook, forgoing “likes,” “favorites,” or “shares” in its design. Are.na allows users to compile uploaded and web-clipped “blocks” into different “channels,” and has been described as a “vehicle for conscious Internet browsing,” “playlists, but for ideas,” and a “toolkit for assembling new worlds.[2]

How the slowness is practised ❔

⭐There is no endless feed or algorithmic content delivery.

⭐Users curate channels manually, gradually and consciously.

⭐There are no likes, ratings, or engagement metrics.

Why it matters❔:

The platform encourages slow accumulation and rethinking of information, rather than rapid consumption.

📖 Readwise Reader (reading & reflection tool)

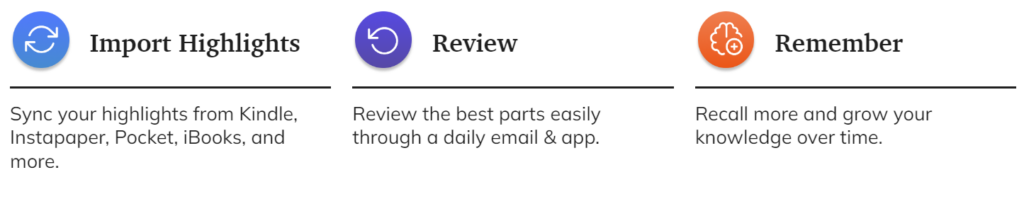

Readwise is a digital tool designed to help you retain and organize the most valuable insights from your reading. Readwise leverages powerful techniques like spaced repetition and active recall to supercharge your memory. Through Daily Reviews, Readwise ensures you regularly revisit key insights from your reading material, perfectly timed to enhance retention. This prevents knowledge from slipping away and keeps your memory sharp.[3]

How does it work ❔[4]

How the slowness is practised ❔

Readwise has a very calm, understated interface: there are no notifications, endless feeds, or visual tricks that encourage rapid scrolling. Instead, the app encourages thoughtful, sequential reading. An important feature of Readwise is the ability to return to texts over time: saved fragments and notes periodically reappear, inviting you to reread and rethink them. As a result, reading ceases to be a one-time activity and becomes a longer, slower process of reflection, where understanding and memorization are more important than speed and quantity.

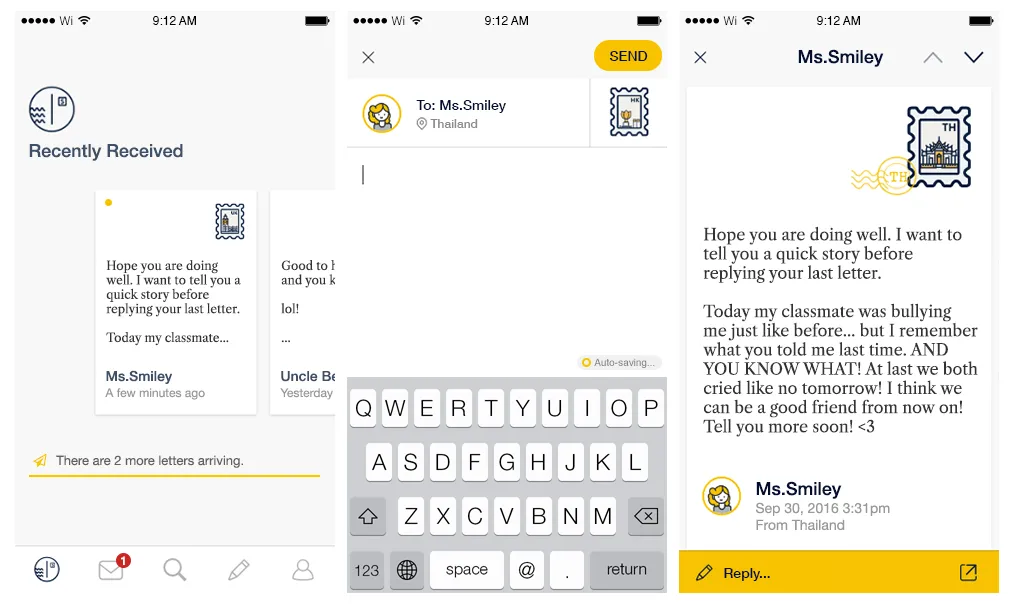

📩 Slowly (intentional communication app)

Slowly is created for those who yearn for the meaningful conversations that are lacking in the era of instant messaging. It connects people around the world at a slower but better pace.

Meet a new pen pal, seal your letter, and stamp it—start connecting with the world on Slowly![5]

I love this app! I meet the most wonderful people in a longer format, more curious, more meaningful context. I’ve met people who live across the river and across the ocean from me, and we are all so similar. — Paula Anderson [6]

How does it work ❔

Unlike instant messengers, messages do not arrive instantly: delivery time depends on the distance between the correspondents and can range from several hours to several days. This deliberate slowdown changes the very attitude towards communication — letters are written thoughtfully, not impulsively, paying attention to wording and meaning rather than speed of response.

This approach reduces the pressure of constant availability and the expectation of immediate responses. Communication becomes more conscious and emotionally rich, and the pause between messages ceases to be “empty time” and becomes part of the experience. Slowly shows that digital products can support depth and trust not through acceleration, but through rhythm and anticipation.

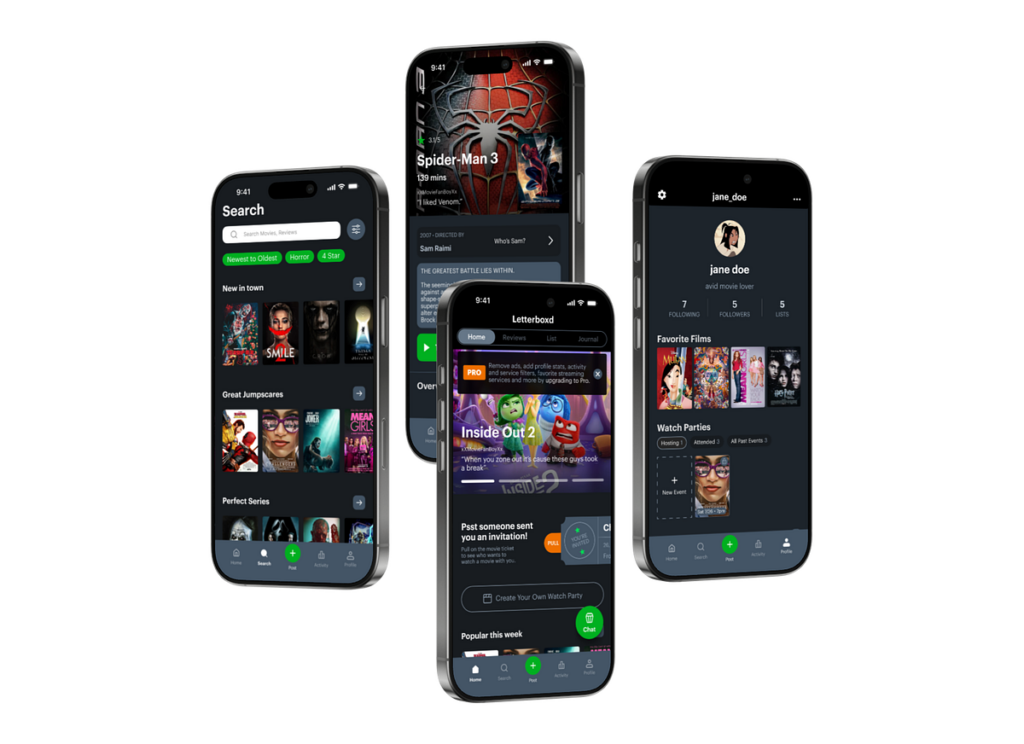

🎞️ Letterboxd (platform for mindful viewing and reflection on cinema)

Letterboxd — is not just a service for marking watched movies, but a space for a slow approach to media. Instead of clip consumption, it encourages users to record their impressions after viewing: users write notes, return to movies, and build their own history of taste over time. There is no pressure to rush — you can’t “scroll through” a movie, and feedback only appears after the experience is complete.[6]

How the slowness is practised ❔

⭐Interaction occurs after watching the film, not during.

⭐The emphasis is on reflection and forming an opinion, not on instant reaction.

⭐No endless consumption or autoplay.

⭐The profile functions as a personal archive of experiences, not as a quick content feed.

Sources 🛈

[1] Forest App. Forest: Stay Focused — About the App. Seekrtech Co., Ltd. Available at: https://www.forestapp.cc/

[2] Are.na. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Are.na

[3] Readwise Docs. What Is Readwise? Readwise Documentation, 2025. Available at: https://docs.readwise.io/readwise/docs

[4] Readwise. Home Page, Readwise, 2025. Available at: https://readwise.io/

[5] Slowly. Home Page, Slowly, 2025. Available at: https://slowly.app/

[6] Letterboxd. Home Page, Letterboxd, 2025. Available at: https://letterboxd.com/